By: Isha Kumari

If history were khichdi, it would be an uneven mix – a spoonful of brilliance, a dash of bias, and a bitter aftertaste of forgotten names. We often raise our glasses to Newton and Einstein, Tesla and Hawking, rendering them as the founding fathers or crème de la crème of STEM, as if the world of science spun solely on the axis of male genius. Which is why it doesn’t come as much of a surprise when people think that most scientific developments, if not all, have been shouldered by men because women simply do not have the intellectual capacity to achieve such things. However, irony dies a thousand deaths when you start to scrape through and see that behind many celebrated “lone visionaries”, often stood a woman whose ideas were borrowed, buried, or quietly erased from the footnotes of progress. It’s not that women didn’t contribute towards science and technology, it’s that history consciously decided to forget to CC them on the recognition email.

The idea that women lack the ability to grasp numbers or make sense of complex technical matters, has been a tasteless stereotypical joke, which despite all the strides we’ve made in society with regards to feminism, somehow still continues to prevail. Take for instance Ada Lovelace, who wrote the first-ever computer program in 1843, a time when computers weren’t even in existence. While working for Charles Babbage on his Analytical Engine, she realised that machines can do way more than mere calculations, they can be trained to perform complex instructions. Today, she is finally recognized as the world’s first computer programmer, but that acknowledgment took more than a hundred years to arrive.

During World War II, thousands of women worked as ‘human computers’ calculating ballistic trajectories for the Allies, and programming the earliest electronic computers. Among them were the six women who programmed the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), the world’s first general-purpose electronic computer, built for the U.S. military to calculate artillery firing tables during WWII. For decades, their names – Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas, and Ruth Lichterman were absent from historical records. The machine was hailed as an engineering triumph, but the women who made it function were not even invited to its public debut.

Not to mention, the much talked about space race wouldn’t have taken off without Katherine Johnson and her all-female team of mathematicians at NASA, who crunched the numbers that sent rockets into orbit.

Then there were brilliant minds like Hedy Lamarr, a 1940s Hollywood actress by day and inventor by night, who co-created a frequency-hopping system that paved the way for Wi-Fi and Bluetooth.

One of the greatest discoveries in modern science was the DNA helical Model by Watson and Crick who were awarded a Nobel Prize for it, no less. But how many people actually know that the model was based on an X-ray diffraction image (Photograph-51) taken by Rosalind Franklin. Franklin’s jealous colleague Maurice Wilkins showed her photograph to Watson and Crick without her permission and ended up receiving the Nobel Prize along with them, while Franklin remained unrecognized during her lifetime and eventually succumbed to cancer she likely developed due to the excessive radiation exposure she had received while taking the photograph.

Another tough lady inventor was Stephanie Kwolek who invented the Kevlar fibre, a key material used to produce products like bullet-proof jackets, combat helmets, ballistic face masks and rocket parts. Kwolek herself worked for years with little fanfare and no share of the billion-dollar profits her discovery generated.

The women of India were not far behind in pushing the boundaries of science and technology, proving that brilliance knows no gender and innovation knows no borders.

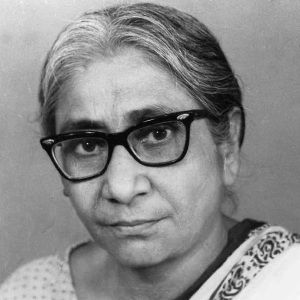

Take for instance Dr. Asima Chatterjee, an Indian organic chemist, who was brewing up lifesaving anti-malarial and anti-epileptic drugs in her Calcutta lab, at a time (1950s) when most women weren’t even allowed near a Bunsen burner, let alone a science lab in India.

Fast-forward to the 21st century and come witness India’s Mars Orbiter Mission (Mangalyaan) be guided by two remarkable women: Ritu Karidhal, known as the “Rocket Woman of India,” and M. Vanitha, the mission director. Together, they helped India reach Mars on the very first try, and on a smaller budget than most Hollywood outer-space movies.

Women have come a long way, but the road to recognition in science is still under construction. They are yet to reach a satisfactory pedestal, when it comes to taking their rightful place in the world of science, particularly in STEM, which accounts for less than 30% of the global female workforce. From the labs of India to the corridors of NASA, they have defied odds, shattered stereotypes, and built innovations that the world often took for granted. The journey is far from over; but with each discovery, each breakthrough, and each young girl inspired to follow in their footsteps, the pedestal inches closer to where it truly belongs: a place of recognition, respect, and equality.